An interactive map, based on publicly available documents, displaying locations and elevations relevant to the disappearance of B-24 #42-41081 on March 22, 1944, the discovery of the crash site, and recovery of remains from Mount Thumb, New Guinea thirty-eight years later. Zooming in on Mt. Thumb will show the reported crash elevation contours.

The Owen Stanley mountain range on New Guinea claimed many Allied aircraft during WW2. Early in the war, airplanes had to cross this range from bases in Port Moresby to conduct attacks against Japanese installations, maritime shipping and naval forces that were operating along the north coast and in the Bismarck Sea.

The weather could be very changeable over the mountains and horrific storms with swirling clouds, punishing winds, heavy rain, and even icing conditions, could be encountered there without much warning. Winds could be strong enough to turn an airplane upside down and downdrafts could cause a rapid loss of altitude. Either situation could cause a plane to meet up with the “rocks” that were hidden in the clouds.

This summary is based on the contents of a Missing Air Crew Report, a 1982 news clipping from The New York Times, a three-piece series that appeared in The New Yorker magazine in 1986, a 1986 newspaper clipping from The Victoria Advocate, and a clipping from the Leader-Telegram newspaper. The Leader-Telegram piece was used the least as many of the details seemed to have been confused with some other crash.

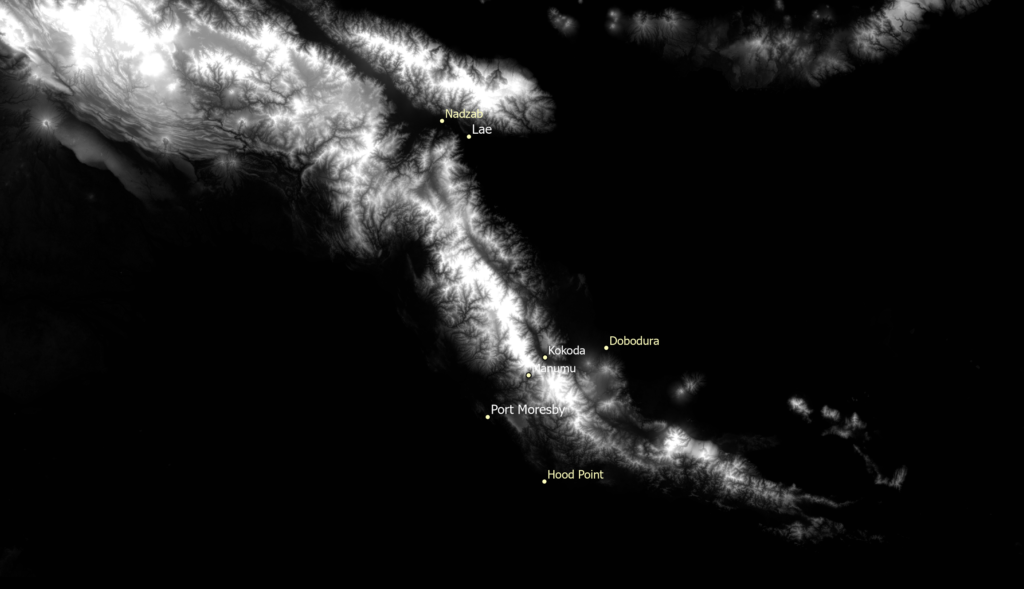

V Bomber Command of the 5th Air Force operated a replacement and training center out of Jacksons Drome in Port Moresby. They used a variety of aircraft types to train new aircrews and ferry them to their duty stations at more forward bases. A B-24D from the 90th Bomb Group, tail number 42-41081, was in their fleet and was scheduled to fly an administrative flight from Port Moresby to Nadzab on March 22, 1944. Along with the crew of three, nineteen passengers, some of them new replacements on their way to 345th Bomb Group, others returning from leave or a hospital stay, crowded aboard the plane. Because of questionable weather along the most direct route through “The Gap”, a route taking them southeast to Cape Hood, north to Dobodura and then on to Nadzab was advised.

A newly arrived B-25 crew was also scheduled to fly a new B-25 to Nadzab to join the 345th Bomb Group. The co-pilots of the two planes were requested to change places to put an experienced pilot in each, so 2Lt Raymond J. Geis took his place in the right seat of the B-24. Engine trouble delayed the takeoff of the B-24 until mid-afternoon and #42-41081 was last seen that day by the control tower operators as it took off from the airdrome.

Thirty-seven years later, hunters from the remote village of Manumu found the wreckage strewn about on the steep slope of a ridge high up on Mount Thumb. Months later, the US Army Central Identification Lab, a predecessor of the DPAA, was made aware of the discovery and then visited the site in 1982, at which time they recovered human remains. The elevation of the crash site was just below 8,400 feet (8,856 feet by one account). Months were spent sorting the remains in a laboratory but twenty-two sets of remains were finally declared as identified using a wide variety of forensic techniques.

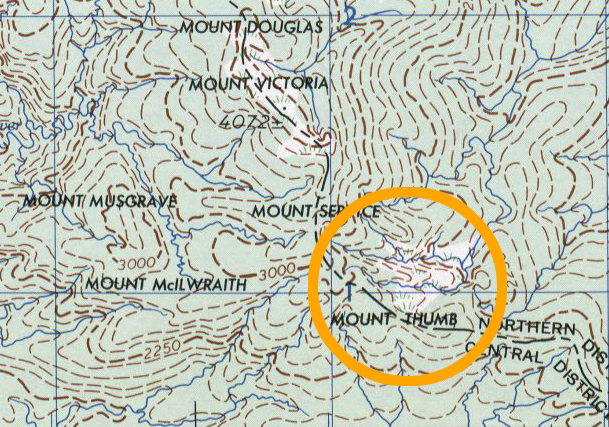

Mount Thumb does not seem to be notable enough to be labelled on satellite imagery, but I found it on several old maps. Unfortunately, the labels for the mountains were placed in general locations instead of showing where the highest points were located. The section of map below calls out the general location of Mount Thumb and indicates a grassy area above it.

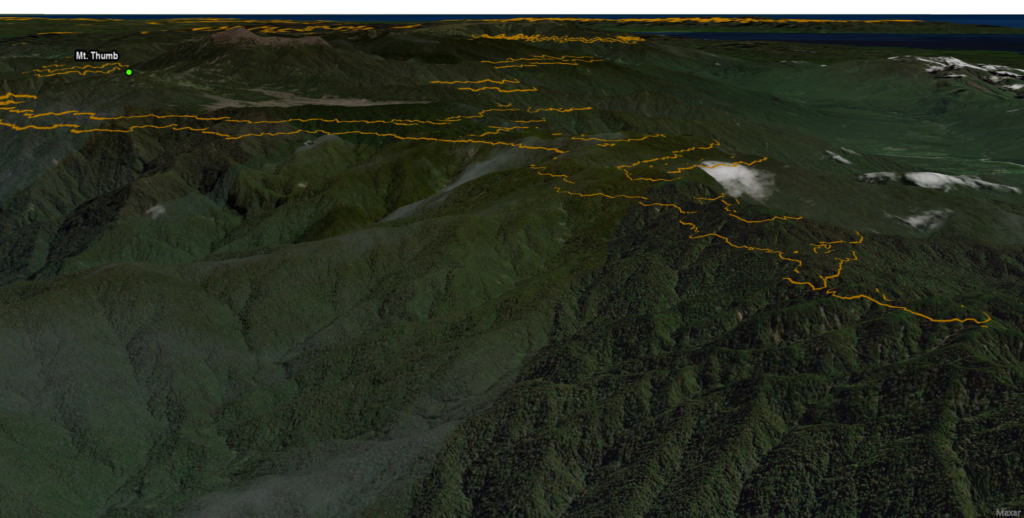

From the location of the wreckage on Mount Thumb, it became clear that 2Lt Allred, the pilot of the B-24, had decided to disregard the routing suggestion, perhaps because of the late takeoff time, and instead tried to fly a more direct route from Port Moresby to Nadzab over the mountains and perhaps by planning to fly through “The Gap”, near the village of Kokoda. The section of map below shows both Mount Thumb and “The Gap”.

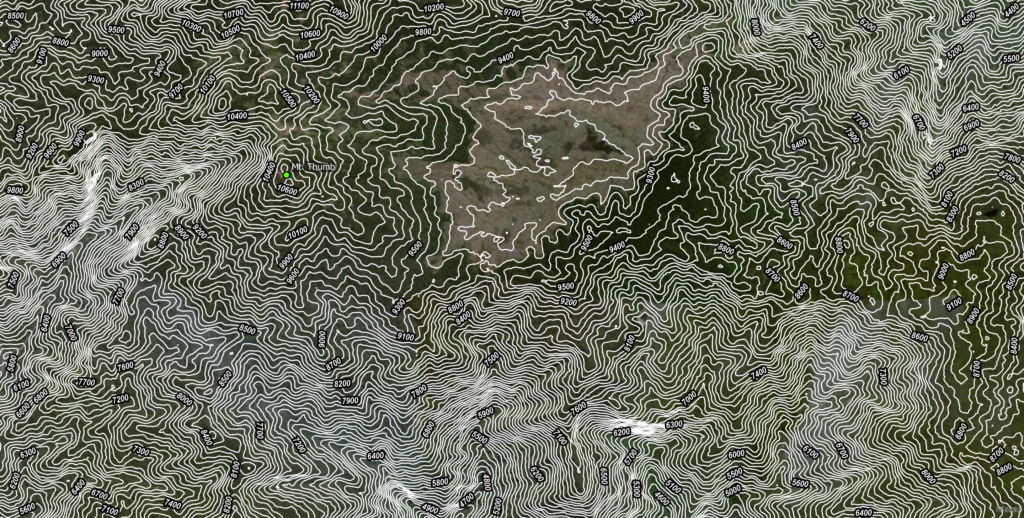

To find the summit of Mount Thumb, I used a Digital Elevation Model (DEM) that was produced from data recorded by NASA’s TERRA satellite using an ASTER sensor; a joint project of the Japanese and American space agencies. The DEM not only provides an image, but contains unfathomable quantities of elevation data, which can be accessed by mapping software.

Using the elevation data of the ASTER dataset, contour lines were created for the Mount Thumb vicinity. By using a contour interval of one hundred feet, the highest point was found to be about 10,700 feet, which was close to the 11,000 foot elevation mentioned on the wikipedia page for the mountain.

To provide a less cluttered view of where the crash site could be located, 1,000 foot contour intervals were created over the imagery and then separate contours for the 8,400 foot and 8,856 foot crash elevations were added. [A three-part article by Susan Sheehan in the March 1986 issues of The New Yorker magazine reports the 8,400 foot elevation while a May 3, 1982 story in The New York Times places the elevation at 8,856 feet.] While I have no coordinates for the actual crash site, it would seem likely that it is somewhere along the ten mile stretch of those elevations along the south side of Mount Thumb. The description of the crash site being just downhill from a temporary landing zone and camp site used by the investigators suggests that there would be a relatively flat area at the stated elevations (for landing a helicopter and pitching tents) that would then drop off, almost precipitously, to the wreckage field. A stream ran along the bottom of the ravine that held the wreckage.

Whether the crash elevations that run to the southeast of Mt. Thumb are considered part of another mountain or Mt. Thumb is not clear from the available map data. I have included them because of their continuity with the Mt. Thumb elevations and the possibility that, if Lt. Allred was trying to fly through “The Gap”, they could have become unseen obstacles.

Lost with B-24D #42-41081 and then recovered were:

- 2Lt Robert E. Allred, pilot**

- 2Lt Raymond J. Geis, Jr., co-pilot *

- 2Lt Keith T. Holm, navigator **

- Capt Charles R. Barnard, passenger ****

- 2Lt Stanley G. Gross, passenger *

- 2Lt Harvey E. Landrum, Jr., passenger *****

- 2Lt Charles R. Steiner, passenger *

- 2Lt Melvin F. Walker, passenger *

- 2Lt Emory C. Young, passenger *

- 1st Sgt Harold T. Atkins, passenger «

- 1st Sgt Weldon W. Frazier, passenger ««

- SSgt Thomas J. Carpenter, Jr., passenger *

- SSgt Frank Ginter, passenger ****

- SSgt William M. Shrake, passenger *

- SSgt John J. Staseowski, passenger *

- SSgt Robert C. Thompson, passenger *

- Sgt Clint P. Butler, passenger *

- Sgt Stanley C. Lawrence, passenger ***

- Sgt Charles Samples, Jr., passenger *

- T/4 Joseph E. Kachorek, passenger ««««

- Cpl Joseph B. Mettam, passenger *

- Pfc Carlin E. Loop, passenger «««

(*345th Bomb Group **22nd Bomb Group ***38th Bomb Group ****43rd Bomb Group *****82nd Reconnaissance Squadron «670th Anti-Aircraft Machine Gun Battery ««665th Anti-Aircraft Machine Gun Battery «««565th Signal Air Warning Battalion, medic ««««5th Field Hospital, medic)

In 1983, their remains were interred individually in private, national, or overseas military cemeteries, in accordance with the direction of next-of-kin.