The foundation of my research into the WW2 345th Bomb Group is a group of large files available on the 345th Bomb Group Association website. These files are scans of mission narrative report documents that were written soon after the mission debriefings were completed. These reports contain information as to the mission target, participants, the attack plan, the results of the attack, and often a map of the route to and from the target and another of bomb placement on the target. Some of these reports are easy to read while others suffer from poor quality, but, that is what there is to work with until someone finds original paper copies in an archive somewhere and makes high quality color scans of them. Deciphering the poorer quality images became an investigative adventure in itself and caused me to learn a lot about comparing typeface and making inferences from those similarities.

Reading through the mission narrative reports, I recorded data in a spreadsheet that soon became long and very wide since I was treating each mission as a single row of information. During the 2010 reunion in St. Louis, Missouri, I found that another researcher had made an amazingly similar spreadsheet for the 500th squadron and we shared our results. It only took a tiny bit of tweaking to get the two styles to merge seamlessly into a spreadsheet that covered all the missions mentioned in the narrative mission reports for all four squadrons of the group.

Locating the mission targets on Google Earth and capturing the geographic coordinates then became a priority. Many of the mission narrative reports contained target maps which, along with the text of the report, allowed a set of coordinates to be determined for each mission. Not all mission narrative reports have these target maps included and not all are as detailed as the one below.

WW2 era topographic maps were often helpful in locating the targets described in the narrative reports. As the war progressed, more and better maps were available to the air crews for navigation and target identification. Digital copies of some of those maps are available, which can make assigning target coordinates much more accurate for some missions.

Both the mission and topographic maps could be used as an overlay in Google Earth to help place the targets for gathering coordinates.

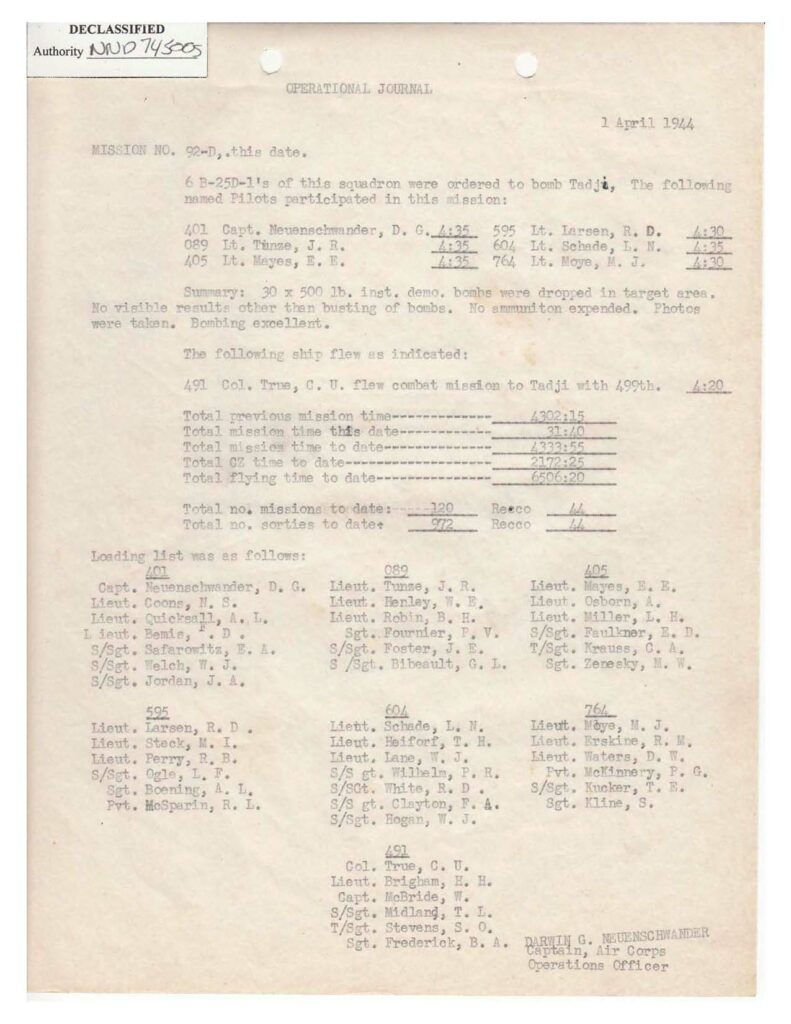

Another valuable document is the Operational Journal, or what has come to be referred to as the Load List. These daily documents list all the flight crew members for each airplane flying that day. These can be very helpful in tracing the history of individuals. Unfortunately, not many of these documents have been recovered from the National Archives. Several members of the 345th Bomb Group Association have spent some time at the archives and recovered many load lists for the 500th and 501st Squadrons. I could not find any of the lists for the 498th or 499th Squadrons.

From what I have noticed on the load lists, the crew members are always listed in the same order. Officers are listed first, starting with the pilot, the co-pilot, then the bombardier/navigator and any officer observer. The enlisted crew are listed beginning with the engineer, then the radio operator, aerial gunner, and then the combat photographer or enlisted observer.

Friends from the 345th sent me a spreadsheet they had developed from the load lists found at the archives. Their version listed each airplane participating in a mission on a separate row and it was much easier to manage as a database and to display on maps. Adapting the original spreadsheet style to theirs took some time, but it was definitely worth the effort. The result was a searchable database.

A few words about airplane numbers. Each airplane was assigned a build number by the manufacturer. A serial number, often referred to as the tail number, was also assigned to each airplane. This number is generally in the format of ##-#####, such as 41-30040. According to Joe Baugher (of joebaugher.com, a website with extensive lists of military aircraft serial numbers), the first two digits represent the fiscal year when the airplane was ordered and the last five digits are the airplane’s sequence within that fiscal years order. In the load lists and mission narrative reports, each airplane is usually referred to by the final three digits of the tail number. In the 345th Bomb Group, the last six digits of the tail number were stenciled on the outboard surfaces of the vertical stabilizers, although later in the war some airplanes only had the final three digits displayed. Airplane identification can become an issue as replacement airplanes sometimes had the same 3 final digits in the tail number, which can lead to some confusion unless you have access to a listing of the airplanes and their dates of service.

Bringing together all this data from reports, maps, books and websites has made the map making projects much more efficient. Having all the data in a database has also made it possible to search for mission information for any particular day, airplane, target, or named crewman.