When the 345th Bomb Group first started flying missions in New Guinea during June 1943, they were mostly assigned to fly submarine patrols over convoys in the Coral Sea and re-supply missions for ground troops operating along the coast of the Huon Gulf.

On June 27, 1943, four B-25s of the 500th Bomb Squadron were assigned to drop supplies to troops operating in the Pilimung village area, about fifteen miles inland from Salamaua. According to statements in the missing air crew report, the B-25 flown by 1Lt Lee A. Ow was last seen entering a cloud in a valley near Pilimung and did not return to the base in Port Moresby. A month later, an Australian Infantry unit reported finding a crashed B-25 and the remains of three crewmen (from a crew of four). The crash site was reported as being five miles from Pilimung, but no compass direction was provided. No tail number for the airplane was noted on any of the documentation.

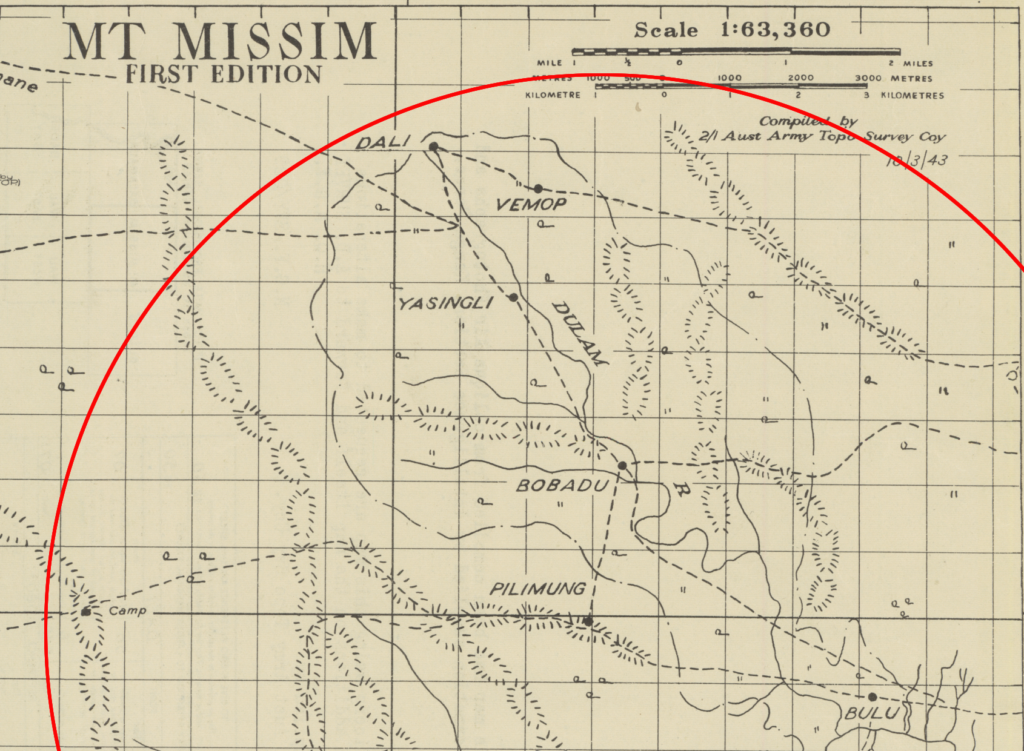

Using a 1943 Australian Army map of the Mount Missim area, I created a circle centered on Pilimung with a five mile radius. The result was a roughly eighty square mile area in which the crash could have occurred.

I recently received a digital copy of the Individual Deceased Personnel File for Lt Ow. While most of the documents in the IDPF were related to dental charts, personal effects inventories, and re-interments, two of the pages listed his place of death as being Doli, New Guinea. A village named Dali was located close to the five mile radius north-northwest of Pilimung which suggested that Lt. Ow crashed near there.

The village locations on the 1943 map are quite different from what sites like Google Earth and Mapcarta offer. Part of that, I’m sure, is because villages in a slash-and-burn culture move every few years after the jungle soil is depleted in their gardens. These villages could have moved many times in the eighty years since the Australian map was compiled and there are many small, treeless scars across the landscape that could have been village or garden sites. Another mapping attempt, using the current coordinates for the villages, could prove interesting.

It also possible that the 1943 map is completely wrong due to the remote, rugged, unexplored nature of the area. Fortunately, the current and former locations of Pilimung are reasonably close which allows for a good approximation of the five mile radius and a crash site estimate. Several uniquely shaped riverbends and junctions that have been preserved in the mountainous terrain provide a level of confidence when transferring locations from the map.

In the placement most of the village locations onto the satellite imagery, river bends and junctions were compared between the 1943 map and satellite imagery. In placing the Dali village, the shape of the dash-dot-dash form line on the 1943 map and contour lines created from a digital elevation model on the satellite imagery were compared for similarities. Dali village lies outside the five mile radius using this method, but that could be at least partially explained by not knowing the map projection used to create the 1943 map.

On 3D imagery of the Dulam River valley looking upstream from Pilimung, there are many valleys into which Lt. Ow might have flown as he left the supply drop target at Pilimung. The available documentation does not indicate the flight direction over Pilimung or whether the cloud he was last seen flying into was a small patch of mist or if it was part of a more extensive cloud layer. Inclement weather had been the cause for several incomplete supply missions during this time.

The elevations in this part of the Dulam River valley range from 2760 feet at river level below Bobadu, to 4700 feet at Pilimung, to 8700 feet in the mountains that form the end of the valley above Dali. Since the 345th crews were very inexperienced flying in the weather and terrain of New Guinea in June 1943, a possible cause for the crash could be that the pilot was not expecting to find rocks in the clouds.

According to an article in The Quartermaster Review, September-October 1945 issue, available through the Army Quartermaster Museum at Fort Lee, Virginia, aerial resupply drops were usually made from an altitude of two hundred feet over target. If this B-25 was attempting to climb after making their drop, they would have had less than two minutes to gain enough altitude to clear the mountains beyond Dali. With a climb rate of 1,100 feet per minute, this B-25 might have run out of time to gain enough altitude. But, any attempt to determine the cause now would be mere speculation.

Lost in the crash were:

- 1Lt Lee A. Ow, Jr., pilot

- 1Lt Joseph D. Rosenthal, bombardier-navigator

- TSgt Merle W. Guyer, radio operator

- Sgt George E. Miller, armorer gunner

Lieutenants Ow and Rosenthal are buried in private cemeteries in the US while Sergeants Guyer and Miller are buried in the Manila American Cemetery in the Philippines.